Letter to Democratic Republic of the Congo president hailed as historic by Belgian media

King Philippe of Belgium has expressed his “deepest regrets” for acts of violence and brutality inflicted during his country’s rule over Congo, as the Democratic Republic of the Congo marks the 60th anniversary of its independence.

The letter to the DRC president, Félix Tshisekedi, has been described as historic in the Belgian media, as it is the first time a Belgian king has expressed regret for the country’s colonial past, although it stops short of an apology.

In the letter, the king writes of “painful episodes” of the two countries’ shared history, referring to the Congo Free State run by his ancestor, Léopold II, whose brutal exploitation of the territory is estimated by some to have caused the deaths of 10 million people, and has become the subject of fierce debate amid the Black Lives Matter protests.

Without naming Léopold II, King Philippe writes: “During the time of the Congo Free State [1885-1908], acts of violence and brutality were committed that weigh still on our collective memory. The colonial period that followed also caused suffering and humiliations. I would like to express my deepest regrets for the wounds of the past, the pain of today, which is rekindled by the discrimination all too present in our society.”

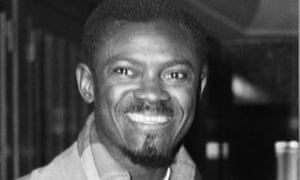

After Léopold II was forced to give up Congo as his private fiefdom in 1908, the Belgian state ran the country until 30 June 1960. Belgium ceded control of the vast territory soon after Patrice Lumumba, a charismatic independence leader, became Congo’s first democratic prime minister. Lumumba was assassinated in 1961 by Congolese rebels and Belgian army officers on the orders of the CIA, with the tacit support of the Belgian government.

Martin Fayulu, a respected opposition politician in the DRC, said it was never too late to recognise past wrongdoing and called for reparations from Belgium. “If they recognise now what they did here, then that’s all to the good, but these can’t just be words because that’s what it’s fashionable to say at the moment. But that’s the past. It’s what they do now that matters.”

Fayulu, the leader of the Engagement for Citizenship and Development party, said the anniversary of independence made him angry. Many observers believe the 63-year-old veteran politician easily won elections held in 2018 but was excluded from power by the current president, Félix Tshisekedi. Fayulu rejected the official tally, saying it was the product of a secret deal between Tshisekedi and the outgoing president, Joseph Kabila, to cheat him out of a clear win.

“The looting of the Congo has never stopped. Our resources are stolen, our people remain in misery, we are ruled by dictators and thieves. The international powers say they need to be pragmatic. And look where we are.”

Tshisekedi, who heads a coalition government, has called for a day of “meditation” rather than celebration, and will address the nation on Tuesday.

Josue Cibwabwa, 28, a shopkeeper and pro-democracy activist in Mbuji-Mayi in the Kasai-Oriental province, said the call for meditation was welcome. “Congolese people should really ask themselves what their country will become in the future,” he said. “Citizens should be asking more from their leaders. The DRC is at a crossroads.”

Jerome Ongome, an 86-year-old retired teacher living in Bukavu, told the Guardian politicians had promised “heaven on earth” once Congo was free of colonial rule. “Before independence, our politicians promised … Congolese would drive cars and get higher salaries. I am now retired without driving or any income,” he said.

“I remember my father saying the exploiters were leaving. There was a sense among the people of Congo that suffering had ended.”

David Luta, a 23-year-old student from Fizi in South Kivu province, said that despite the irregularities surrounding the election last year, he was happy that there seemed now to be “a political plan for the future”. “The fact that Kabila transferred power peacefully to Felix Tshisekedi give us young generation hope for the future,” he said.

Despite massive natural wealth, including vast deposits of valuable minerals and precious metals, the DRC continues to suffer from deep poverty, widespread violence and disease.

The king’s letter contrasts with the recent remarks of his younger brother, Prince Laurent, who said he did not see how Léopold II could have been responsible for widely reported atrocities in the Congo Free State because he never set foot in the country.

Belgian commentators have been struck by the contrast with King Philippe’s predecessors, who ignored colonial violence. At an independence day event in Léopoldville (now Kinshasa) on 30 June 1960, King Baudouin declared that Congo’s self-determination was “the outcome of the work conceived by Léopold II”, while praising his ancestor’s “tenacious courage” as “not a conqueror, but a ‘civiliser’.”

Echoing some of the king’s words, Belgium’s prime minister, Sophie Wilmès, called for recognition of past suffering without making an official apology. “As with other European countries, the time has come for Belgium to embark on the path of research, truth and memory.”

The death of George Floyd in the US has rekindled anti-racism protests in Belgium, prompting the federal parliament to set up a “truth and reconciliation” commission to “come clean” about the country’s colonial past.

Belgian politicians suggested the king’s statement stopped short of an apology, because he did not want to preempt the commission’s work.

Belgian anti-racism campaigners had set 30 June as a deadline to remove all statutes of Léopold II. Across Belgium, colonial-era monuments and busts have been toppled, burned or daubed with red paint or slogans in support of the Black Lives Matter movement.

On Tuesday, a bust of Léopold II that had been vandalised several times was removed from public display in the city of Ghent after a brief ceremony, Associated Press reported. Earlier this month Antwerp authorities removed a statue of Léopold II that had been set on fire and severely damaged. The statue is to be restored, but is likely to be placed in a museum, rather than returned to its pedestal in a city square.

One Brussels politician who has been campaigning for better understanding of Belgium’s colonial legacy said it was “too early” for royal apologies. “I think that the king did well not to apologise immediately,” Kalvin Soiresse, a Green deputy in the Brussels region parliament, told Belgium’s Francophone public broadcaster RTBF. “The parliamentary work is necessary to establish the facts. It is after the establishment of the facts that we can talk about apologies or reparation.”

Soiresse, who was born in Togo, also spoke of how he had received racist abuse because of his work.

Since you’re here …

… we have a small favour to ask. Millions are flocking to the Guardian for quality news every day. We believe everyone deserves access to factual information, and analysis that has authority and integrity. That’s why, unlike many others, we made a choice: to keep Guardian reporting open for all, regardless of where they live or what they can afford to pay.

As an open, independent news organisation we investigate, interrogate and expose the actions of those in power, without fear. With no shareholders or billionaire owner, our journalism is free from political and commercial bias – this makes us different. We can give a voice to the oppressed and neglected, and stand in solidarity with those who are calling for a fairer future. With your help we can make a difference.

We’re determined to provide journalism that helps each of us better understand the world, and take actions that challenge, unite, and inspire change – in times of crisis and beyond. Our work would not be possible without our readers, who now support our work from 180 countries around the world.

But news organisations are facing an existential threat. With advertising revenues plummeting, the Guardian risks losing a major source of its funding. More than ever before, we’re reliant on financial support from readers to fill the gap. Your support keeps us independent, open, and means we can maintain our high quality reporting – investigating, disentangling and interrogating.

Every reader contribution, however big or small, is so valuable for our future. Support the Guardian from as little as $1 – and it only takes a minute. Thank you.